For several decades, this vast change, almost revolution, which took place in the peninsula from the Ionian to the Alps, found no serious obstacles on the part of the kingdom and the empire. No serious attempt to prevent the Norman conquest, nor the now too autonomous life of the cities to the detriment of the prince’s rights, nor the vast usurpation that cities and castles and feudal lords were making of the great Matildina inheritance. In Germany, there is a conflict for the kingdom that Lothair and Conrad contend for. There is a descent of Corrado in Italy, who is crowned king in Monza (1128) as the successor of Henry V, tries to get his hands on Matilda’s assets, tries an expedition to Rome. Other and major intervention by Lothair, a few years later, also at the urging of Pope Innocent II who claimed the papal throne for himself, against the antipope Anacleto II. There were two powerful families in Rome, the Frangipane and the Pierleoni; two contending parties; now, two popes (1130). The Italians also divided themselves, Christian and Catholic Europe were divided. He kept Lothair for Innocent, who, then, forced to flee from Rome, went first, on Pisan ships, to France, then to Germany; they held the Swabians for Anacleto. Many municipalities, too, followed Innocenzo; with Anacleto, on the other hand, Ruggiero di Sicilia and Puglia stayed. Who, entering into this dispute between the pope and the pretender, between aspirants to the crown of Italy and the empire, between partisans of the pope and the antipope, was crowned king in Palermo by an envoy of Anacleto. They collapsed quickly, after the coronation,

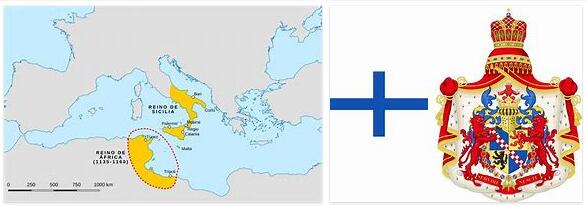

According to REMZFAMILY.COM, they rose again, however, shortly after, when Lothair, called by serious interests of the kingdom and induced by Innocent II, went down to Italy, arrived in Rome even through the opposition of many Lombard cities, and in Rome he had the imperial crown (1133) and the investiture of Matilda’s assets: which also meant a vassalage relationship of the emperor towards the Holy See. But with the emperor retired, the pope had to flee again to Pisa: whence he incited a more energetic war against Ruggiero. A vast coalition had formed against Ruggiero in which, with the pope, Lotario, the Pisans, the Apulian and Campania cities, the southern barons, even the Greeks, in short, all the Italian and European interests, old and new, used to contend for the South or, in any case, averse to the consolidation of that kingdom. Lothair also returned: and this time, without too many contrasts of Lombard cities. They pushed south together. And here they invested in Puglia Rainolfo, the Normans Drengot, playing on the non-extinct antagonism between the two families and contrasting the minor ones with the major ones. In July 1137, the two supreme hierarchs held a great court in Melfi. But, interrupted the enterprise, Ruggiero reappeared, recovered Puglia, restored the fortune of the kingdom, despite the fact that Innocent, in the Lateran council of 1139, still excommunicated him. At that time, moreover, Rainolfo died. And then the pope, left without hope, bowed to peace, recognized Ruggiero and invested him with what he possessed, except for Benevento who remained at the Holy See. To the other lands, the king had already added, by concession of Anacleto, the principality of Capua, which belonged to the Normans of Aversa but was now in the grip of anarchy, and the city of Naples which was governed by its own ducal family. Now Ruggiero took on his definitive title: “king of Sicily, duke of Calabria and Puglia”. It is the end of city autonomy in Southern Italy, although municipal spirits persist, ready to resume and take off in the crises of the monarchy, at the end of the 12th and 13th centuries.

The work begun by Guiscardo and Ruggiero is completed: better, well underway. Not everything was solid in this new building. That barony was always powerful and treacherous. The Holy See always boasted rights over the kingdom and, as Benevento had encouraged against Pavia, so, even more so, did the barons against the king who resided in Palermo. However, for the first time after 570, the political power of a vast region was seen to gather in one hand and achieve a degree of independence and freedom from the interests of other kingdoms and countries, such as it had never had, nor will have more after the Normans. The state formed a single body: first the approach of distinct parts, then a more organic unity. Feudalism found a certain firmness and its own order, as indicated by the catalog of the barons, compiled between 1160 and 1170. It laid its foundations, even on land prepared by Rome, Byzantium, the Lombards, the Arabs themselves, that monarchical sentiment of the South which will give its own character to the whole history of the region. The new building was essentially rising above the pre-Muslim and prelongobard institutions, that is, on the Roman ones modified by Byzantine law. Even feudalism, whose seeds pre-existed the Normans (patronage, commendatio , immunity, etc.) and to which the Normans then fed their traditions and their men, was linked and subordinated to the king. It was the same anti-feudal effort with the weapon of Roman law, which in the meantime in the center and in the north also the cities were making: a common trait, which brought these different parts of Italy closer together, albeit so differently oriented as to political institutions.