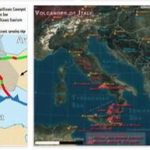

Julius II had died, while by now those “barbarians” whom he wanted to expel from Italy, but who too vice versa recalled the things of Italy, dominated it. And Leo X of the Medici family, who succeeded him, juggled the various potentates, especially between France and Spain. Fluctuating and ambiguous policy, both because the situation is difficult and because the objectives are too many and contradictory. Leo X wanted to prevent, with the help of Spain, a French recovery, weaken the position of the potentates in Italy, obtain good advantages from both sides for the Church and the Medici. Who had returned to Florence. But they had, and their pope for them, other and greater ambitions. Leone was thinking of Milan for his nephew Lorenzo, in Naples for his brother Giuliano, when Ferdinand the Catholic died. Even the Emilian cities, which the Church wanted to claim for itself, but, appetite as they were by the lords of the Milanese or held by the Este family, could not return to the orbit of the ecclesiastical state, could be assigned to another Medici. An arduous undertaking, this of being able to contain the strength and impetus of great monarchies and nations that have now launched themselves into the Italian and European primacy contests. Francis I, the new king of France, began to undertake the title of Duke of Milan with ardor for the enterprise of Italy. Great military device, diplomatic preparation, renewal of the alliance with Venice. In addition to the extermination of the Turks, a coalition of Spain, Austria and the Swiss opposed him, “in defense of the freedom of Italy”. And the pontiff also joined, after he had in vain negotiated with Francis for consenting to his nepotistic plans. But the king of France won, on 13-14 September 1515, the Swiss salaried by Leo X and Maximilian of Austria in Marignano, and expelled them from the duchy. The Swiss lost both the fame of their invincibility and the ambitious hopes for the Milanese. Only they kept the Canton of Ticino. The French settled again in Milan; Massimiliano Sforza also ended his life, like his father, in captivity in France. The pope had to come to terms with the king, compromise on the question of Gallican freedoms, release the cities of Emilia to him, put in his protection the Medicean interests that were at heart no less than those of the Church. Again Italy was divided as into two spheres of domination and influence: the south, Spanish; the north and the center, French. But undeniable prevalence of France. And that king tried to consolidate such a position, perhaps trying to satisfy, to the detriment of still independent Italian states, the aspirations of other competitors. He concluded a treaty with Spain in Noyon, August 1516, for perpetual peace and defense of the respective states; a no less perpetual peace concluded in November with the Swiss, hitherto bitter opponents of French domination in Lombardy; an agreement made with Maximilian in Brussels in December, which was followed by conferences and secret pacts between Francis I, Maximilian and Charles of Habsburg, archduke of the Netherlands and heir of Ferdinand the Catholic in Aragon, Sicily, Sardinia, Naples. This time great things were sketched out: a kingdom of Italy, from Friuli to Pisa and Siena, made almost entirely of Venetian remains, for Charles of Habsburg; a kingdom of Lombardy, from Mantua to the Piedmontese Alps, with Milan, Monferrato, Asti, Genoa, for France. Both, fiefdoms of the empire. Thus, once the three major potentates of Europe had been pacified, their disputes settled in Italy, a great bone of contention, the peace of the world could be considered assured, and a common enterprise could be thought of against the infidels.

In 1519, according to ACEINLAND.COM, a great event took place: Charles of Habsburg, who had already taken possession of the kingdom of Aragon and had also been proclaimed king of Castile, succeeded, with his brother Ferdinand, his grandfather Maximilian in the Austrian dominions; and shortly thereafter, he ascended to the kingdom of Germany. Thus Italy, which had hitherto been confronted with Austria and Spain, now saw the interests and rights of both states in Italy cumulated in a single dynasty. Among the ministers and advisers of Charles V, there is an Italian, Mercurino Arborio di Gattinara, a Turin lawyer and jurist who had already entered the service of the Habsburgs and climbed very high in Burgundy. Appointed by Charles Grand Chancellor of his kingdoms, overcoming the avarice of the Flemings and the national concerns of the Spaniards who feared for the stock market and for the things of Spain, Mercurino worked to obtain King Charles, in competition with Francis I of France, the election as king of the Romans, which meant emperor. And he succeeded, in 1519, then also rising to the dignity of grand chancellor of the empire. Old ideals survived in him: pope and emperor in agreement, peace and religion promoted, the world under one shepherd: in short, the universal monarchy. Two parties were with Charles in the imperial council, after the election of 1519: full agreement with France; war on France. And this second party prevailed, thanks to the Gattinara who headed it, which found a good game in the equal tendencies that prevailed among Francis I. Pope Leo. Truly, the kingdom of Naples and the Milanese in the hands of a single lord; and this same lord, master of so many kingdoms beyond the Alps and invested with the empire, was not something that could satisfy the pontiff. He contravened the old policy of the Holy See, the recent agreements of Julius II with Ferdinand the Catholic, on the occasion of the investiture of Naples given to the king of Spain. But Leo X had to put a good face on the new situation. Also because it was also necessary, in Germany, to face Luther. Thus, in May 1521, a few days later, on the one hand Charles banned the heresiarch from the empire, on the other Leo placed Milan and Genoa under his high authority. The Emilian cities were returned to the pope, Charles assumed the protection of the Papal States and the Medici. With the pope’s money they would have hired Swiss people to recover the Milanese. Vast war. Among the enemies of France, also the king of England who, interposed as peacemaker, was persuaded precisely by Gattinara, envoy of Charles V, that Francis I was responsible for the break. Thus, the Milanese was taken back to the French; on November 19, Francesco Maria Sforza, with the Swiss, returned to Milan and richly donated the Grand Chancellor. The French were for the third time expelled from Italy. At this point, Pope Leo died. And some of Charles V’s gains were lost. But his fortunes did not stop. In January 1522 one of his creatures ascended to the papacy, a Flemish former tutor and, ultimately, his lieutenant in Spain, Adrian VI.

There was an Italian and especially Roman reaction to this rise of Hadrian VI which is very significant. By now everyone considered the papacy to be an Italian thing, and Rome, the city of Italians par excellence, linked to it by ideal and sentimental interests as well as practical. Now, seeing on the throne of San Pietro this unknown “barbarian et baylo de l’Operator”, as Sanudo says, aroused a sense of surprise and almost dismay. In the financial, artistic, magnate, popular circles of Rome and Italy, in the midst of the phalanx of men who lived in the curia and the curia, it was feared that the new pope would not even come to Rome, that he would keep the court closed, would surround himself of Flemings. Even the cardinals themselves, who had made the election, were also discontented and astonished. It wasn’t just about crumbling offices. Keep that sense in mind, then more and more diffused, of a growing threat that was gathering on Italy from foreigners. And also that pride and presumption of the Italian literary world, which easily clashed and reacted to any disavowal of others.