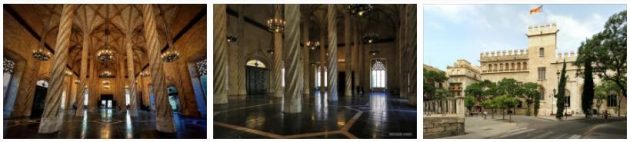

The 15th / 16th The silk exchange, built in the 19th century, is a reminder of the golden age of the trading city. The complex of tower, hall of the marine consulate, orange tree courtyard and columned hall is a masterpiece of secular Gothic.

Silk Exchange in Valencia: Facts

| Official title: | Silk exchange “La Lonja de la Seda” in Valencia |

| Cultural monument: | Silk Exchange – also known as Lonja de Marcaderes – with the Sala de Contratación, the tower that served as a prison for insolvent merchants, and the Consulado del Mar, originally the seat of a commercial court for the settlement of disputes in maritime trade |

| Continent: | Europe |

| Country: | Spain |

| Location: | Valencia, north of Alicante, southeast of Madrid |

| Appointment: | 1996 |

| Meaning: | a late Gothic masterpiece and evidence of the prosperity of a Mediterranean merchant town of the 15th and 16th centuries. |

Silk Exchange in Valencia: History

| 1469 | Decision to build a new exchange |

| 1482 | Laying of the foundation stone for the construction of the silk exchange |

| 1483-98 | essentially construction of the silk exchange |

| 1498 | Construction of the Consulado del Mar |

| 1506 | Death of the builder Pere Compte, who planned the silk exchange |

| 1548 | Completion of all construction work |

| 1921 | The “courtroom” is decorated with allegories |

Haggling under the dragon’s mouth

José Soler Siuranca was seated at seat 73. To his right, at desk number 72, José Vicent Dolz took a seat. They took off their hats with dignity, sorted weighty papers, nodded briefly and firmly to each other. Candles flickered in huge chandeliers high above them. Like almost a hundred other traders, they waited for the bell to strike. Finally a usher stepped into the right corner of the room by the main entrance and solemnly rang the bell: Trading in the Valencia Stock Exchange was open.

This may have been the case for many centuries since the trading exchange was opened on March 19, 1498. However, Valencian merchants met much earlier to exchange their goods. The “Llonja de l’Oli” existed as early as the 11th century, although it wasn’t just oil that changed hands. This trading center soon became too small, and the city leaders reacted promptly: In decades of construction, a huge, rectangular building was built, which to this day rises to a height of more than 17 meters in the middle of Valencia’s bustling old town. Exactly opposite is the vegetable and fish market, where the small traders have always offered their goods.

The major merchants who increased their prosperity with valuable goods may have felt small in view of the huge stock exchange building. This “trading house” looks very ornate, in the upper part almost a little playful. According to mathgeneral, the Valencian coat of arms is emblazoned on every corner, carved from stone. At the top, the Lonja is even “defensive”: battlements and machicolations threaten the worst to potential attackers. In addition, stone dragons swallow something indefinable – greedily opening their mouths – little devils crouching over the few windows, looking menacing and grim. The building doesn’t look inviting, and maybe it shouldn’t be.

Whoever entered through the three meter high doors must inevitably have felt tiny. Inside, the Valencian merchants awaited a notice posted at a height of eleven meters, to which everyone had to submit: No trader should mouth the fraud, and everyone should swear to meet his obligations and never to lend his money with usurious interest. He who heed this would enjoy great wealth and, last but not least, eternal life. In such a mood, the merchant was finally allowed to concentrate on his business, and only on it.

Compared to the exterior facade, the interior of the stock exchange is much simpler. The floor was tiled with alternating light and dark marble, the walls, on the other hand, are largely unadorned. Nothing, it seems, should distract the merchants from what they are actually doing. Those who were looking for diversion could go into an adjoining small garden. There a small fountain splashed peacefully, the scent of orange trees beguiling the tense nerves. And whoever needed divine assistance visited a small chapel. This was located below the defense tower, called El Torreón, in an adjoining room. Skilful latticework still separates mercantile bargaining from religious contemplation.

A third room, El Consulado del Mar, can be reached by stairs. In earlier centuries a kind of supervisory authority oversaw the Valencian affairs of sea trade there. The high-ranking gentlemen not only sat physically separated from the stock exchange, they also had time to think carefully about their decisions. The architect Pere Compte, who was responsible for the interior design, did not see the danger of a distraction: the incredibly artistically crafted ceiling decoration is as if made to lose yourself in it with astonished looks. Even José Soler Siuranca and his neighbor could not have concentrated on trade here.