Even the political balance of this troubled era does not end with the list of provinces that came into the hands of Spain. The long wars also had their fruitfulness. Not everywhere has the process of forming territorial states with their own governments and dynasties been disturbed and interrupted. Wars have provided opportunities and created resolved needs in favor of some of these states, which are a little offspring of the storm. According to LOCALTIMEZONE.ORG, the Duchy of Tuscany, later Grand Duchy, would not perhaps have been established without the favor and cooperation of Spain who disarmed Pope Medici in this way and took away traditional friends from France, right in the heart of Italy, namely Florence and then Siena, the last representatives of municipal freedoms and municipal spirits, with the relative inability of wider state organization. He took himself forward, like this, the work to which the Florentine republic had so many times and in vain put its hands, defeated more quickly than done, that is, the political unity of the region: useful to prevent Spain from spreading even further in the peninsula. Also the duchy of Parma and Piacenza and the wider dominion of the Gonzagas, to whom Charles V gave and Philip II confirmed the Monferrato, were born in the brake or in the service of Spain, to weaken or strengthen the position of Spain in Italy. For if these two small states did not represent much in that unitary process of the peninsula, in that growing adaptation of political Italy to the Italy of culture, which are the central fact and the common thread of Italian history; more important was that Genoa was able to remain relatively independent and have the support, diplomatic if not military, Spain to recover Corsica from the hands of the French, which was a strip of Tuscany and Italy in terms of language and civilization. Even more important was that Philip II, after the victory of St. Quentin by Emanuele Filiberto, agreed in his favor to return the Piedmontese lands that France had occupied in ’36. His task had to be to guard the Alpine passes, to watch the Milanese from France, in short to make a country that, from the time of the Angevins onwards, had become, more or less according to the times, an open field to the benefit of the crown and its Italian politics. French action, and the basis of the military undertakings of the King of France. Now, with the treaty of 1559, Henry II only managed to keep the marquisate of Saluzzo: which should not have displeased Spain, as a means of keeping the Savoy more attached to it; not to the friends of the “liberty of Italy”, because a remnant of counterweight to Spain was maintained in the peninsula. In short, the kings in contention, especially Spain, if they had what they had, had to compromise on the rest, obtain solidarity, count on friends made powerful, as well as on subjects. And some progress in the political organization of the peninsula resulted. Everything was done with a view to another’s interest, that is, a Spanish one. But it is natural that, once those political organisms were created or strengthened, they went their own way; and in addition to solving more or less political-social problems of a local nature, as well as advancing political education and a sense of the state in the Tuscan or Piedmontese people, they concurred to keep the Spaniards on target, to corrode their power and prestige, ultimately to demolish them in the dominion of Italy.

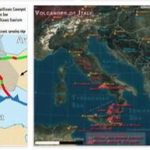

And the State of the Church? At the beginning of the century, France, allied with the Borgias, had helped the popes to reclaim cities and provinces from local tyrannies: and Julius II, the major builder of the State of the Church, had well exploited the Italian and European greed unleashed against Venice, to get back the cities of Romagna. Since then, other storms have poured over this state, rendered ill-still by organic incapacity and the object of bitter irony on the part of Machiavelli’s subtle spirit. But his weakness was also his strength. The nature of the power that personified that state, if it made it unable to defend itself with weapons, assured it of guarantees of another nature. And now, in the century. XVI, there is like a consecration of the State of the Church, like a halo of holiness that surrounds it and defends it: “Benefit” attached to the apostolic office, inseparable from it and inviolable. The renewed spirituality of the Church and the papacy also affects its earthly dominion. Thus it was able to carry out that task for which the Italians of the 16th and 17th centuries praised it: to be a barrier to Spain, a wedge between the Milanese possessions and the Neapolitan possessions of Spain.