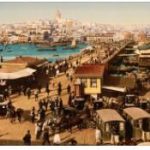

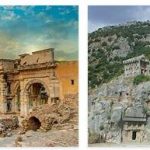

The historic districts of Istanbul are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Some of the ancient squares are still recognizable in today’s cityscape: the Severan Tetrastoon from the 2nd century AD (later Augusteion), the Hippodrome (203 AD, enlarged after 324), the Forum of Constantine (early 4th century AD). Chr.), The Theodosiusforum (327–393), the Philadelphion, the Arkadiosforum (435 AD). Various honorary columns and arches have been preserved, as well as the snake column from Delphi (479 BC), the Gothic column (332 AD) and an obelisk from Karnak (15th century BC) on an antique base (probably 390 A.D.). The Valens Aqueduct (368 AD) is well preserved, which, as part of the aqueduct built under the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens (364–78), bridged two of the seven city hills of Constantinople and 920 m of which, originally over 1,000 m, are still preserved. Various cisterns as well as parts of the remains of the Byzantine city walls and gates are also well preserved. The Constantinian sea wall on the Golden Horn once had 110 towers, the Constantinian wall on the Marmara Sea (with pre-Constantine parts on the palace area) 188 and the Theodosian wall (413; fortifications) 96 towers. 439 missing connecting pieces were created between the walls. Some of the foundations or mosaics of the ancient palaces were exposed.

According to Recipesinthebox, the most important late antique Byzantine church building, the Hagia Sophia, like other Byzantine churches, was converted into a mosque; some are now museums, others are still fully used as mosques. The Küçük Ayasofya (Little Hagia Sophia) was built as Sergios and Bakchos church probably before 532; The octagonal interior with its two-storey column architecture is famous (changed 1506–13, the old mosaic and marble decorations were lost). The construction of the Zeyrek Camii dates back to the early 12th century when the southern church was the first of the three side-by-side churches of the Pantokrator monastery to be built; the middle church is important as a Byzantine burial place. The Fethiye Camii was started in 1050 as the church of the Pammakaristos monastery (burial chapel 1315, outer narthex after 1326); the church of the choir monastery (originally probably 5th century) experienced since the 11th Century changes and modifications to the Kariye Camii (Byzantine mosaics and wall paintings, around 1300). The Kilise Camii was built in the 11th-14th centuries. Century (mosaic remains); the İmrahor Camii (collapsed in 1894) was set up in the Johanneskirche (463) of the studio monastery, the ruins of which still reveal the three-aisled gallery basilica with narthex (as part of the atrium). The series of large Ottoman buildings began with the conqueror’s foundation complex Mehmed II (1463-70; the Fatih Camii was rebuilt after the earthquake with a modified plan 1767-71) on the site of the demolished Apostle Church of Justinian I.

On both sides of the mosque, 16 madrasas were originally arranged in symmetrical rows. The influence of the vault system of Hagia Sophia is first palpable in the mosque of Bajasids II. (1501-06), it subsequently found multiple variations (Süleymaniye Camii, the mosque of Sultan Süleimans I, 1550-56, and Kılıç Ali Paşa Camii, 1580, – both works by Sinan) or were modified to form a radially symmetrical quatrefoil: Şehzade Camii (1544–48, by Sinan) and the Ahmed Mosque, the Blue Mosque (1609–16, by Mehmed Ağa, a student of Sinan); a preliminary stage can be found in the three-pass scheme of the vault of Iskele Camii Sinans in Üsküdar (1547).

Especially for foundations of the grand viziers there is also the scheme of T-shaped mosques adopted from Bursa (Mahmut Paşa Camii, 1462; Atik Ali Paşa Camii, 1496), as well as – based on the model of Üç Şerefeli Camii in Edirne - the scheme of the on Six-point main dome (Sokullu Mehmet Paşa Camii, 1571, by Sinan), which with two accompanying smaller secondary domes only required two cantilevered pillars or columns (Sinan Paşa Camii, 1556; Atik Valide Camii in Üsküdar, 1570–83; both by Sinan). But the scheme of the multi-domed mosque was retained well into the 16th century (Zincirlikuyu Camii, around 1500; Piyale Paşa Camii, 1573). The simple type of single-dome mosque (Firuz Ağa Camii, 1491; Bali Paşa Camii, 1504; Haseki Hürrem Camii, 1539; by Sinan) was monumentalized (Sultan Selim Mosque, 1522) and connected to the eight-pillar system (Mihrimah Camii, around 1556; Rustem Paşa Camii, 1561, both by Sinan; Mesih Mehmet Paşa Camii, 1585; Yeni Camii, 1597–1663, by students of Sinan; and Laleli Camii, 1759-63). After the Nuru Osmaniye Camii (1748–55), the mighty baroque single-dome mosque became the preferred type of historicizing architecture of the 19th century (Nusretiye Camii, 1822–25; Ortaköy Camii, 1854). The six-pillar type (Kara Ahmet Paşa Camii, 1553–55; İvaz Efendi Camii, around 1585, both by Sinan; Hekimoğlu Ali Paşa Camii, 1584–87; Eyüp Sultan Camii, 1800) was developed.

While the early Ottoman architecture in Istanbul still showed massive structures, the influence of Hagia Sophia soon became clear; Beginnings can already be seen in the Bajasid mosque; in essence, it was the Sinan’s accomplishment to dynamize space. In the course of the 18th century, the “Ottoman Baroque” emerged under Western influence; Leading the way was the Balyan family of architects, who have been active for several generations. These massive buildings with a western face, which were laid over Ottoman floor plans, shaped the image on the banks and hills of the Bosphorus (Dolmabahçe Serail, Selimiye barracks); some of them are built directly on the waterfront on the bank walls. Towards the end of the 19th century, the predominantly foreign architects decorated the buildings with elements that were understood as “oriental” (imperial medical school in Haydarpaşa, Sirkeci train station).

The Italian architect Raimondo D’Aronco (* 1857, † 1932) introduced the design language of Art Nouveau. At the beginning of the 20th century, the “First National Architecture” movement emerged, represented by Kemalettin (Vakıf Hanları, near Sirkeci Train Station) and Vedat Tek (large Istanbul Post). In the 1940s, a second national trend emerged, and less strict solutions were now introduced in residential construction (Sedad Hakki Eldem). Since the 1960s, Turkish national architecture has opened up to the international design language of modernism. With the demolition of almost all wooden houses in the old town, which are being replaced by new residential and commercial buildings, with spacious street openings and the construction of new districts and business centers, the cityscape is becoming increasingly international. After the demolition of many Gecekondu settlements, entire districts are radically redesigned.

Together with Essen and Pécs, Istanbul was European Capital of Culture 2010.